Good morning from St. Louis, Senegal. I type this entry on my iPhone, which is never fun, from the room of my current CouchSurfing host, Mayoro. Mayoro is a 27-year-old St. Louis native, who works in an NGO caring for abandoned children, manufactures djembes (Senegalese drums), and snugly fits the profile of the quintessential Rasta–dreads, red/green/black beanie, Bob Marley t-shirt–the whole thing. He lives with his family, maybe 10 people in total, in a house that’s been with them for more than 5 generations. There’s a large sandy courtyard area, with a water spout, clothing lines, a bathroom for bucket showers, a stone toilet (flushed with a bucket as well), 2 large baobab trees, several goats (which bleet incessantly), and a few cats. It’s a relaxed place: la vie africaine, as Mayoro puts it. We speak French and talk Senegal.

On December 19th, I arrived in Nouadhibou, Mauritania. I’ve been traveling overland since Stockholm, and man, Nouadhibou looks nothing like Stockholm. Donkey pushcarts run the streets, and camels roam the outskirts. The city has trash everywhere, sand everywhere, and no discernible charm. At the very best, Nouadhibou carries an ironic, post-apocalyptic romanticism–like that closing scene in Fight Club, but without the girl. At worst, it looks like a bomb had leveled the whole city a few short years ago. Nouadhibou was not pretty, and it reeked of fish.

Sunset in Nouadhibou, Mauritania.

My plan was to spend only 2 days and 2 nights, and prepare myself for the train to Choum. As mentioned in previous posts, the train transports iron ore in the Choum-Nouadhibou direction, so when it runs in the direction I’d be riding, it’s empty: passengers can ride in the empty ore cars, under the stars and free of charge. In fact, you can even ride on top of the ore when the car is full, but that just seems like a whole different level of “dust gets f*cking everywhere.” The train itself is over 3 kilometers long, making it, I believe, the longest and heaviest train in the world.

To prepare, one needs a turban, to cover their face, and an empty flour sack, to cover their backpack. The morning after arriving in Nouadhibou, at around 11am, I set off to look for the above.

After 30 minutes of walking, I was stopped by a woman and her young daughter. “Hi. Come have a tea,” she said. “I own a restaurant around the corner.”

I obliged, and off we went.

Around the corner, and we enter the restaurant: a small room, with a gas stove in the corner, several large cooking pots, 2 plastic tables, and flies simply everywhere. The woman, from Senegal, promptly hands me a tea, later cafe Touba (coffee from Touba, Senegal–rather ubiquitous, I’d later discover), and even the odd clementine. A few of her family members filtered in and out, and we all chatted for a while. Everyone was extremely friendly.

After about an hour and a half, the woman tells me that her nephews are hanging out at their house down the street, and that I should join. I again oblige. The nephews are Malian, from the other side of the family, and are lying on mattresses watching TV.

I stay for a while, loosely snoozing through some broadcast of the president of France giving a press conference in Algeria, and a documentary about gorillas. Later, the woman’s brother takes me shopping, and I buy my turban, as well as a sack to protect my backpack. I leave around 5, meet two American brothers doing a Morocco to South Africa overland trip back at the hostel, and bring them back to the house for tea around 7, as invited. I brought clementines too–maybe 20.

The night was beautiful. We drank tea, watched 24 dubbed in French, took pictures (many with the young daughter, named Mama-Awa), and laughed for hours. There was more family there this time–we were about 15 in total. The neighbors came over as well, and everyone thoroughly enjoyed themselves.

Around 10pm, we left. The woman’s brother and the Malian nephew walked us outside, and we discussed how we’d get home; myself and the brothers–Andrew and Kevin–were 25 minutes of walking from the house. We made it clear that we could take a taxi, but in the end, the brother and nephew walked us all the way back.

At the door to the hostel, the owner, Ali, asked us about our night. We told him it was great, although one of the brothers mentioned that people had been asking us for money on the street.

“Probably Senegalese,” Ali replied. “They’re always asking for money.”

This, as all racist, ignorant over-generalizations do, f*cking pissed me off. I wanted to say something, about how flawed and inflammatory the statement was unless it holds true for every Senegalese citizen, and how, furthermore, the brother standing right there was Senegalese himself, and hadn’t asked for money all day; in fact, he, and his family, had been incredibly kind and welcoming from minute one.

I decided to hold my tongue, and Ali left just after.

Not 15 seconds later, and the brother turns to me and says: “OK, we walked you here, now give me 200 ouguiyas (Mauritanian currency, roughly $0.75 USD) for a taxi home.”

..

I was fully taken aback, and fully confused. Of course the money was trivial, and I wanted to give it to him, part amicably, and just chalk it all up to some “cultural difference,” but I couldn’t help but feel, very strongly, that the request was misplaced, inappropriate, and flat out wrong.

I declined, and an argument ensued. At first, he had the upper hand–I didn’t really know what to say. After a few minutes, I fired back pretty hard, vehemently deconstructing the last hour: how we offered to take a cab, how we explained that it was far, and how you simply don’t ask someone for money in this situation, as if it was some pre-arranged exchange of service. The Malian nephew was confused himself, squeaking out something to the effect of “I’m sorry, I don’t know why he’s acting this way.”

At the height of my argument, the man walked away, and that was that. The family had previously invited me to stay with them in Touba, Senegal a few weeks later, but I really don’t see it happening at this point. O well.

Lastly, I note that the contrast between the brother asking for money, immediately after Ali irresponsibly shot off about Senegalese people always asking for money, is not one I wish to stress: I’m not trying to show that Ali was right whatsoever. It was one guy, not a whole nation. And that’s just how the story went down.

The next day–armed with turbans, dust shields, bread, Kiri, Nutella and clementines–Andrew, Kevin, and I took to the iron ore train. It was meant to leave at 2pm, so we arrived around 1:30. We showed our passports to the officers in the station, took a few pictures, and waited.

The train arrived at 4:15pm–this is Africa, after all. We climbed up into one of the ore cars–already shared by three 18-year-old Mauritanian students on their way home for the holidays–set down our blankets, made our acquaintances, and got going. The car itself was basic, as advertised–quite literally just an empty, metal wagon. While dust and iron particles tornadoed about, the car was actually cleaned to an impressive standard, given that it was filled to the brim with iron ore a few hours prior. With a turban pulled fully over your face, and with sunglasses on underneath, it was very tolerable.

The journey lasted roughly 13 hours–rail-side police checkpoints included. We caught a beautiful sunset, slept under the stars, and made new friends–barreling through the Sahara Desert all the while. A very unique experience that I won’t soon forget.

At 5:00am, the train stopped. There was no station, no town, no nothing. At best, there were a few lights, a few kilometers ahead. In all extreme likelihood, the train had broken down.

*With tired eyes, little energy, and our stuff strewn everywhere:

Andrew: “Should we go ask if we’re here?”

Kevin/Will: “Haha, calm down man. It’ll be obvious–people will be getting off. Lots of people get off at Choum.”

Andrew: “True, OK.”

The train started moving just a few minutes later. At about 5km/hr, and speeding up, a man walked by.

Andrew: “Excuse me, but is this Choum?”

Man: “Yup, you gotta get off right now. Quickly!”

Shit.

Kevin climbs up the side of the car, we frantically pass our backpacks up to him, and he throws them off the side. Then, he jumps.

My turn–train moving around 10km/hr. I climb up the side, prop my bum on the corner of the car, put one foot on the metal piece connecting our car and the car ahead, and jump myself.

I hit the sand, barrel roll a few times, and pick up my head just as Andrew does the same.

There was another train coming in our direction on a parallel track, and although we were out of harm’s way, I wasn’t sure that my backpack was.

“Where’s my f*cking pack, Kevin?!”

“Back there somewhere!!”

I throw on my headlamp, and start sprinting alongside the track. Maybe 40 meters back, and I see my backpack. I grab it, unharmed, and that was that.

From Choum, there was a Nissan Hi-Lux pickup truck, white and with a double cab, that would take us to Atar, a city of reasonable size and the capital of the Adrar region. We get in the car: Andrew and 5 others in the cab part, and Kevin, myself, and 5 others (including Fumio–a Japanese guy we’d met in the station who’s biking around Africa for 2 years–and Fumio’s bike) squashed into the rear bed of the pickup, and off we went.

The ride began under a bright, starry sky. The sun rose, pink and purple, about an hour later. We zoomed through a desert plateau– massive cliffs on one side, some round boulders on the other side, the odd tree and the semi-frequent cropping of straw huts. The ride was not comfortable–but this is travel.

The team arrives in Atar around 9:15am, and we begin searching for a taxi to our final destination, Chinguetti, where we’d be riding some camels through the Sahara for a few days. We find one quickly and climb in–3 people in the back and 3 in the front–with myself sharing the passenger’s seat with an older Mauritanian man. The 80km ride takes about 5 hours, and, finally, almost a day later, we arrive in Chinguetti. This is travel–travel in Africa.

Once in Chinguetti, we sorted our camel trek for the next day, drank copious amounts of tea, and collapsed in exhaustion. A hell of a journey, and a rest well-deserved.

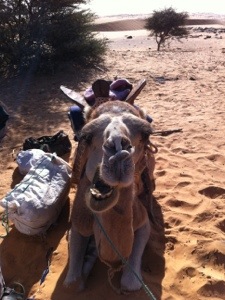

The following afternoon, we headed into the desert: myself, Kevin, Andrew, Fumio, 2 guides and 4 camels, and of course, our respective turbans. My footwear of choice was hiking boots, which were not ideal, but I do think they were a better choice than thongs, which were the only alternative.

The trek was gorgeous. Tall, creamy, elegant sand dunes, with the frequent bush or low-standing tree dotting the view. Kevin and Andrew rode the camels, and Fumio and I trudged alongside.

We walked for only about 2 hours–8 kilolmeters, maybe–and set up camp in a flat clearing. We made pasta for dinner, drank some tea, laughed as our guides (a father and his son) burned through their 4th and 5th hours of non-stop debate (in Hassini, so we didn’t have a clue what they were talking about), and told some stories.

Later, after the guides had gone to sleep, we made more rounds of tea, rolled some relaxation, listened to reggae, and kept the fire going. When the wood burned out, we discovered that dried camel poop burns with equal effectiveness; it’s the carbon, or something.

Sleep happened on my blue foam sleeping mat, in my sleeping bag, and under the stars. The starry blanket of the Sahara Desert.

The following day, after a frequently interrupted, toe-chilled sleep–bread baked in the sun and a lot more

of the sugary, minty, sometimes bitter staple tea, we loaded the camels and headed back into the desert.

The walking–the walking through the desert, that is–was quite nice, and really not so hard. I think I could do a 2-week type trek if I wanted to–physically at least. Without sandstorms, which we didn’t have, desert walking isn’t that difficult.

Around noon, we arrived at the oasis. We didn’t actually go inside, as the palmed, fenced community commanded an entrance fee of 500 ouguiyas (under $2), which we didn’t feel like paying. Instead, we hung out at the perimeter, drinking tea, eating couscous, reading, and lying in the sun.

At 3pm, we headed home. I rode one of the camels for about 45 minutes, but the inside of the saddle was a bit rough on the inner thighs, and I de-boarded. We arrived back at Sheik’s (our auberge) around 4, thanked our guides, and relaxed once more; there’s a lot of relaxing when you’re on the road. Most is deserved, though, if you’re doing it right.

A bit later, myself, Andrew and Fumio went to buy some snacks for the next morning. I quickly bought some dates, a carton of milk, and made my way into the Old Town in search of a mosque that Andrew had read about.

Holy hell, was the Old Town gorgeous. It looked like a fresh archaeological find, a crumbling city made of well-kept sandstone rocks, most buildings without windows and some without roofs. It had a “get lost in the alleyways” type layout, and a Jerusalem type mysticism. A truly beautiful place.

On our way back to the auberge, we traversed the big (very big) sandy expanse–a dried river bed, I believe–that separates the Old City from the New City, and happened upon a few dozen kids playing soccer beneath a gorgeous, intense, ruby-streaked sunset; a calm evening, and a smiling travel moment. This is the life.

The next morning, and it was off to Nouakchott–the capital of Mauritania, and our last stop before heading to Senegal. We took a 5am cab to Atar, as the driver sung morning prayers for the entire 2 hour ride, and quickly found an 8am van to Nouakchott upon arrival.

The van left on time, surprisingly, and the ride that followed was largely uneventful, except for an elderly man and an elderly woman both vomiting on the floor, the car swerving to avoid the odd camel crossing the street, and stopping to pick up the odd watermelon at a police checkpoint. Nobody seemed to care much about the vomit either; the driver didn’t even pull over to clean it up. Dunes lined the tar highway en route to the nation’s capital, punctuated by the odd village and military outpost.

We arrived in Nouakchott around 2pm, I met up with my CouchSurfing host–a German girl named Sam–at the bakery across from the Malian embassy, ate some food–hash browns with eggs dish, some oranges, and cheese fondue–with her, her Algerian boyfriend, Kevin, and Andrew, and grogged my way to an early sleep a few hours later.

A great week in Mauritania, all things considered. A bit too much vomit would be my only complaint.

The next post will likely cover Nouakchott to Dakar. I plan to keep this blog updated in a “From X to Y” fashion for my remaining ~4.5 months in West Africa. I’m keeping daily notes too, so the posts are as detailed as possible.

I finish this post from an old military bunker on the cape of Dakar–the western-most point in Africa. Île de Gorée–one of the first slave ports–is in faint view, and something like Venezuela or Panama is the next stop across the Atlantic. On the outside of the bunker, Entrée Defense–Interdit de Baiser is sloppily written. In English: Defense Entry–F*cking is Prohibited.

Happy New Year all,

Will

Hi Will–

Paul and I loved this post. What a lot of amazing adventures! I don’t know how you will ever return to the sedentary lifestyle in Wynnewood?! I think you will have to start up an NGO in Africa or someplace! As to the remark about the Senegalese and money–well, It’s a little bit true I’m afraid. Not exactly in a bad way though. It’s just that they are soooo poor and mostly illiterate, that they hustle all the time. We still loved it there. Maybe you’ll get down to Popenguine–very nice beach. We stayed at a lodge there owned by a middle aged French woman married to a much younger Senegalese man. Apparently there is a trend in that direction! We also went to Kaolak–one of those dusty, ugly African cities, and about 5 km from there we visited a peace corps worker living in a mud hut. She was one brave young woman! We met her whole village, gave them their pictures we took with our Polaroid, and had a chicken killed and cooked for us before our very eyes–open fire of course. These people lived a lifestyle of permanent camping. Good memories!

We’re planning to go to Vietnam Feb 28-Mar 10, then house trading in Thailand this summer. Our Australian/Beijing traders are in our house in Wynnewood right now while we are down in CC, TX–Paul and Marty went to the beach! Nice weather here for the most part.

Take good care,

Karyn

Thanks a lot Karyn. That sounds like a great lineup.

Have a great time down in CC, and a very happy new year!

I get that he was not entirely appropriate etc. but that cab stunt is taking the jewish stereotype of being cheap to a whole new level

Respectfully I disagree, Winston. Giving money would have left an awful taste in my mouth: as if the day was some mercantile exchange, and their kindness was purely conditional. I still feel he was wrong. He demanded the money too; it was the exact opposite of “hey, I’m exhausted, you mind spotting me this cab ride?”

The actual dollar amount is of course totally irrelevant.

Oh okay that didn’t fully come through in my reading. I can see that being annoying.

But awesome shit would love to ride in an iron ore train some day lol.

Maybe I do it too much but I inevitably think of how much things actually cost and so may come off as insensitive in a poorer country (like in Serbia where I am now). It’s something I’m getting used to.

This sounds like an incredible journey, Will! I’ve heard about this train before, so it’s really fascinating to read your account of the journey. Mauritania won’t be making it onto my itinerary for the time being due to its laws (death penalty for homosexuality), but it’s a country that isn’t often written about. Not sure how I’d have dealt with the vomit. And I DO think that guy was wrong for asking for money, especially if you offered to take a cab before. I’d have been taken aback, too.

Hi Will,

I’ve been loving your blog posts.

I’ve been to lots of places that are not necessarily considered “safe”. But the US State Dept puts a really scary warning on their site about going to Mauritania: terrorism, kidnapping, ISIS, all that jazz.

Can you comment as to the safety? Did you see any sign of extremism? Any places to avoid?

Thanks,

Eric

Hey Eric! There was a similar warning out when I was there.

Nothing out of the ordinary transpired. In fact, the bush taxis I’d ride in — a ~4 hour trip from the interior to the capital, for example — were stopped by police every ~25km (!) such that they could ask the tourists where they were going, if they needed help, etc.

It was a breeze all things considered. Funky country :).